We all want our ideas and plans to make sense. But how do we know that we are making sense? What do we even mean by that? When we use the Thinking Process Tools, we are building a model of the way part of the world works, and in this context our model makes sense if it in does in fact portray a picture of the world that is pertinent and accurate.

To be pertinent, our model must be of that part of the world (our system) that we actually care about in other words our model must have the proper scope. It must not be too detailed in areas that don’t significantly affect the outcome, nor too general, glossing over areas where important details lie. To ensure pertinence, the people who are the main stakeholders in the outcome of the plan must have influence over it.

To be accurate, the cause-and-effect relationships that we model must indeed hold in real life. The Categories of Legitimate Reservation (CLR) are ways to verify the accuracy of a Thinking Process Diagram. They are used to catch common pitfalls in our own thinking and the thinking of others. They are called the Categories because they are well-defined and of limited number. They are called Legitimate because anyone who writes or reads logical statements is always allowed to express them. And they are Reservations because they highlight parts of the diagram that are not completely convincing. Since these reservations are always legitimate, they can be raised, explored, understood, and accepted without anyone feeling like they’re having their toes stepped on. They help everyone keep their emotional distance and stay reasonable.

When you start to work with Thinking Process diagrams, you should deliberately consider the Categories of Legitimate Reservation one by one for each part of your diagram. But as you gain experience you will find you begin to apply them quickly and habitually.

Clarity

If you are creating a Thinking Process diagram by yourself, you probably have a good idea of what you mean. However, you will also probably need to share your plan with someone else sooner or later, and you need to apply the Clarity reservation as the last step before you do. Ask yourself:

- Is the meaning of each part of my diagram clear?

- Is the meaning of my diagram as a whole clear?

Similarly, when someone presents you with a Thinking Process diagram you have never seen before, you should apply the Clarity reservation first by asking yourself:

- Does this diagram really convey what the person presenting it intends?

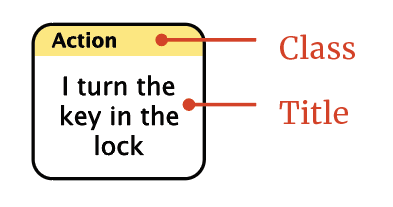

In Thinking Process diagrams, causes and effects are all represented by entities: rectangles that contain brief statements that are, or could be, true about reality. Flying Logic entities also have a colored bar at the top that designates the entity’s class: the kind of role the entity plays in the diagram of which it is part.

To satisfy the clarity reservation, the title of an entity must be:

- complete, unambiguous, and grammatically correct,

- in the present-tense, and

- simple in that it contains a single idea with no compound statements.

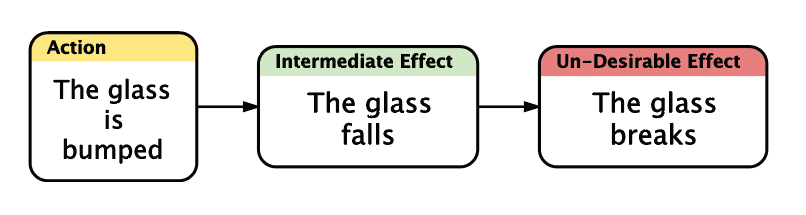

“Bumped and glass fell and broke,” is an example of a statement that violates all three principles. This idea should probably be expressed as three separate entities, each related to the next by a causal connection:

The causal connections between the entities must also be clear, with each step from entity to entity having a natural and obvious flow for any stakeholder who reads the diagram. Reading from one entity to another via an edge (also called an arrow) will follow one of two patterns, or Thinking Processes. Which Thinking Process is used depends on what kind of diagram you are working with; but within a single diagram, the meaning of the edges does not change.

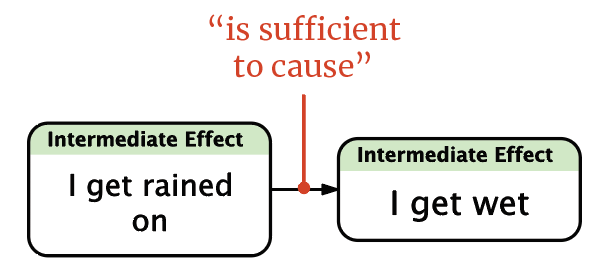

- Sufficient Cause Thinking: “If A then B.” or “A is sufficient to cause B.”

This pattern expresses the idea that the existence of A is, by itself, enough to cause the existence of B. Sufficient Cause Thinking is used by the Current Reality Tree, Future Reality Tree, and Transition Tree.

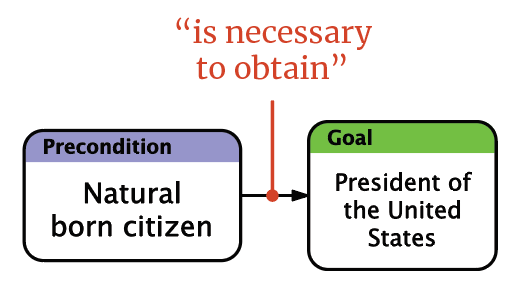

- Necessary Condition Thinking: “If not A then not B.” or “A is necessary to obtain B.”

These patterns express that A must exist for B to exist, but may not be sufficient by itself. Necessary Condition Thinking is used by the Evaporating Cloud and Prerequisite Tree.

Notice that in both illustrations, the edge (arrow) looks exactly the same although the meaning is different. How you read an edge depends on which Thinking Process was used to construct the diagram.

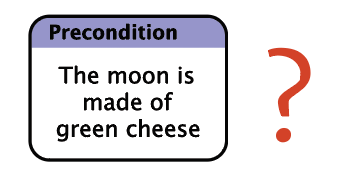

Entity Existence

This reservation asks whether an entity in the diagram is true now. In a Current Reality Tree, for instance, every entity in it should describe something that is true now. A Future Reality Tree or Transition Tree, however, can contain a mix of entities that are either true now, or would be expected to become true under certain conditions. This reservation is a warning to “check the facts” before making an untrue assertion about reality.

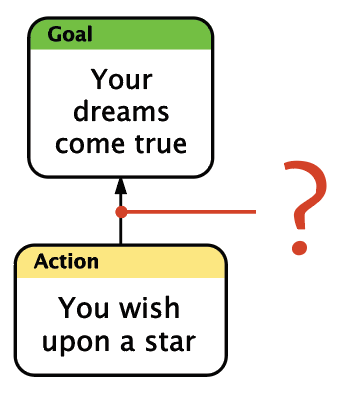

Causality Existence

This reservation asks, “Does A really cause B?” Often we associate two ideas because they are correlated, that is, they are often found in proximity to each other. However, to actually say that one thing causes another requires much stronger evidence.

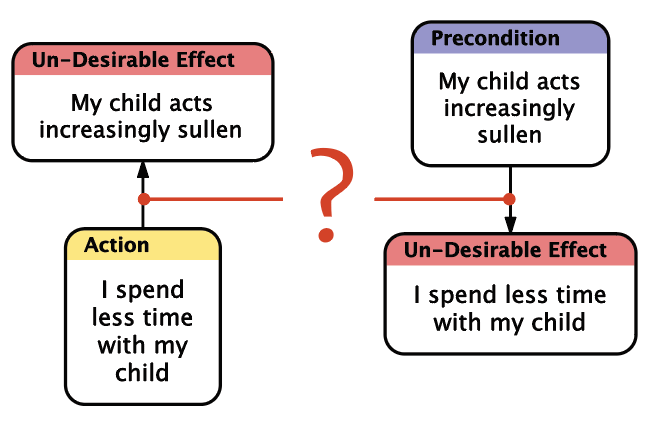

Cause-Effect Reversal

A special case of the Causality Existence reservation is Cause-Effect Reversal. In this case, we question whether the edge is pointed in the right direction.

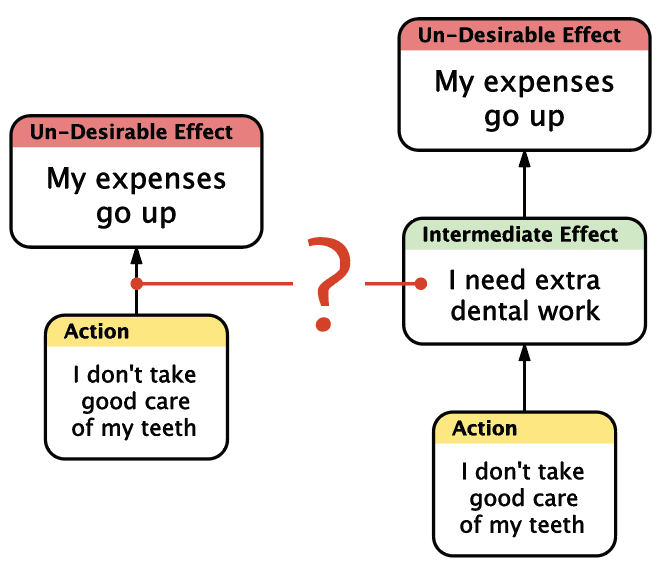

Indirect Effects

Other times, an entity is an indirect effect of a cause, but important necessary steps are missing.

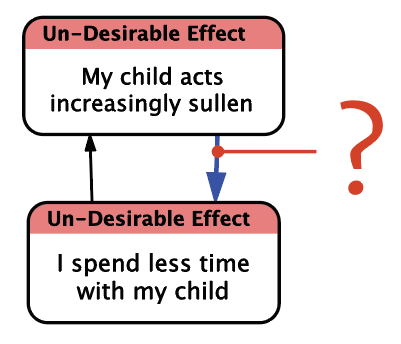

Back Edges

In cases where it seems ambiguous as to which entity is the cause and which is the effect, it may be a good place to look for a self-reinforcing loop. Flying Logic can model self-reinforcing loops using back edges. A back edge is added whenever you attempt to create a new edges that indirectly makes an effect to be its own cause. Back edges are drawn thicker than regular edges.

Insufficient Cause

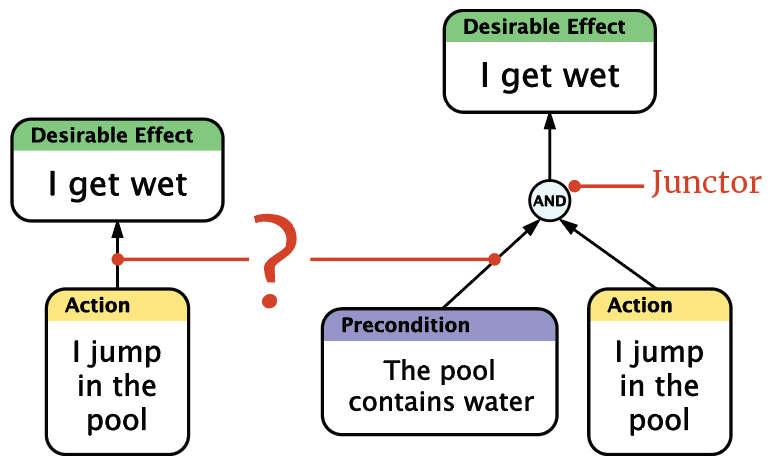

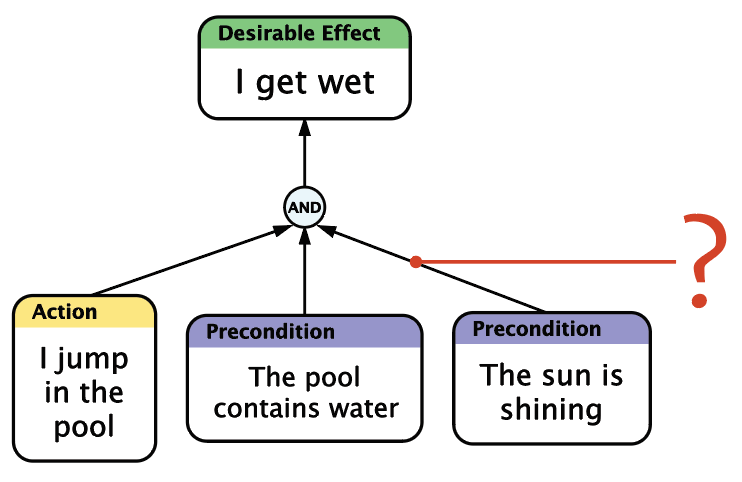

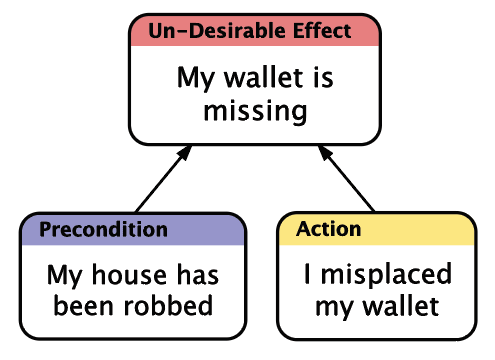

This reservation asks, “Is A, all by itself, sufficient to cause B? What else might also be necessary?” Usually a combination of factors outside our control (“Preconditions”) and factors that we influence or control (“Actions”) must combine to create a particular effect. In diagrams based on Sufficient Cause Thinking, this is modeled using a junctor that contains the AND operator. Junctors are easily created by dragging from an entity to an existing edge.

When looking for insufficient causes, we should also keep in mind that a list of causes can also be too sufficient, or in other words, include causes that are actually not required to produce the effect. So we should also ask, “Have we listed anything as necessary that really isn’t?”

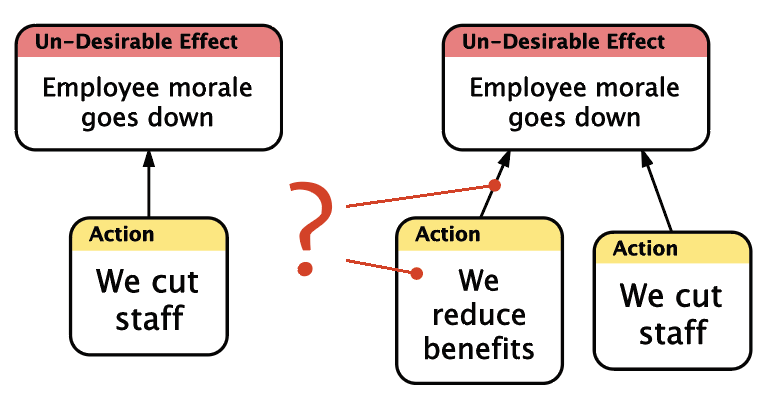

Additional Cause

Once we have identified one sufficient cause for an effect, we are often tempted to move on, and in doing so we may overlook other causes that may either be independently causing the effect, or mutually intensifying it. This reservation asks, “Have we identified every cause of A? What else could also be causing A?”

Predicted Effect

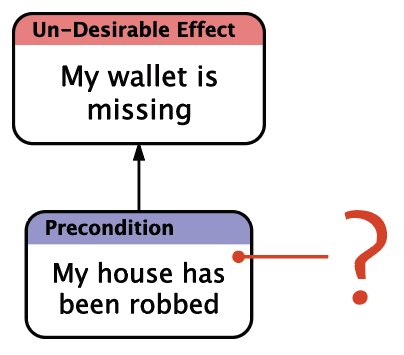

How can we increase our certainty that a cause we have identified is really the cause of the effects we are inclined to believe? For example, let’s say I come from a walk and discover my wallet missing. One of the first things that might pass though my mind is that my house has been robbed. But has it been robbed?

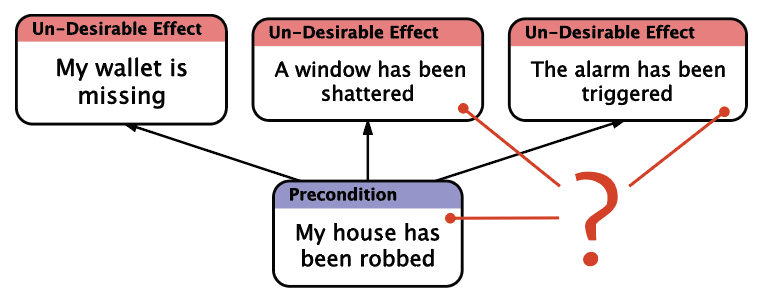

Usually a cause is responsible for more than one effect, and this reservation asks, “If A is true, what other effects in addition to B would we expect to see?”

If the additional predicted effects are also observed, then we can be more confident in the causality we initially identified. But if the predicted effects are not observed, then we may be well advised to look for additional causes.

Tautology

People sometimes don’t examine their beliefs very closely, and will, when asked for a cause, often re-state the cause using different words. Even though you will almost never encounter tautology (also called circular reasoning or begging the question) in a Thinking Process diagram, you will encounter it in casual conversation. Some examples:

- “You can’t give me a C for this course, I’m an A student!”

- “My homework is boring because it’s so tedious.”

- “Mayor Green is the most successful mayor ever because he’s the best mayor in our history.”

- “The defendant shows no remorse, and this fact should strengthen your resolve to find him guilty!”